The lost boys of the Barrier

It was supposed to be an island boot camp to scare youngsters straight. But it spun out of control, scarring many participants for life and prompting comparisons with the classic dystopian novel Lord of the Flies.

The second time Simon visited Great Barrier Island he says was made to dig his own grave. The man with the shotgun who supervised his spadework said: "You think this is a f***ing joke?"

Simon (a court suppression order means the Weekend Herald cannot use his real name) was 15 years old.

It was May 8, 1998, and the boy was one of four who'd escaped from the nearby Government-funded Whakapakari Youth Trust camp. The rustic tent facility was used to hold those too young for prison and as a dumping ground for difficult-to-manage wards of Child, Youth and Family.

The four boys hadn't got far before being recaptured: no one escaped from Whakapakari. The nearest road was a 4km boat trip, or a hike across a thick scrubbed ridge, away. The Coromandel peninsula, the tantalising mainland looming on the horizon, was dozens of kilometres of choppy waves away. This isolation was a boon for containing young people who had a habit of escaping, but some of the boys sent there claim it took on a sinister life of its own.

"The culture of the place ended up a bit Lord of the Flies, to be honest," says University of Auckland social work researcher Dr Ian Hyslop, who has reviewed the facility's files as part of an upcoming job as expert witness for nearly 40 former residents who are suing the Government.

The camp had its own prison island, an isolated rocky outcrop in the middle of Mangati Bay, formally named Whangara, or Cliff Island, but known as Alcatraz.

Despite repeated directives from CYFS head office in Wellington (dating from at least 1988 and continuing until the camp shut down suddenly in 2004) to cease its use, a whole generation of kids claim Alcatraz was used as a dump for camp troublemakers. Many say they were left there, or even dumped into the sea 100m from shore, without supervision or bedding and with only minimal supplies, for weeks at a time.

During their brief, heady, afternoon on the lam the four escapers had broken into a Department of Conservation hut, ransacked a boat, taken a Casio watch, and stolen some marijuana and smoked it. The dope and watch belonged to the man with the gun. He'd demanded from Whakapakari staff, and apparently been granted, an afternoon alone with the petty thieves.

The watch held sentimental value and was said to be a gift from a long-dead mother. The man with the gun, a hard man with tattoos, understood to be a senior gang member, didn't believe the boys when they claimed they'd lost it.

Simon says it was after being interrogated about the watch - which first involved kneeling with gunshots being fired over their heads and later being forced at gunpoint inside a kennel containing a snapping dobermann - that the man brought up grave digging. "The others were digging their holes as well. They were crying. I had just turned 15 - the other boys were younger, 13 or 14. The look on their faces, I'll never forget it. The fear on their faces. We all thought we were going to die," he says.

The boys didn't die that day. Simon told the Weekend Herald they ran for it when the man put down the gun and started waving around a garden slasher.

Interviews with nearly a dozen former Whakapakari residents detail claims of regularised violence, which, though not as lurid as Simon's brush with the alleged gang member, was consistent enough to form part of the everyday background.

They say larger and longer-serving boys were recruited formally as "Young Leaders" and informally as the "Flying Squad", deputised and encouraged by adult supervisors to maintain order through physical discipline.

THE CAMP was finally closed in 2004, after a steady stream of complaints about abuse turned into a torrent. Initial investigations by CYF revealed a third of the boys said they'd been seriously assaulted by staff members. One alleged he had been raped by a supervisor but was too scared to press charges.

Interview notes said many of the boys were traumatised, with one of them telling his social worker: "Before I went to the island I was different, always laughing. People say I'm different now."

The camp had long had a mixed reputation among social workers. It was known as rough and ready, but also one of the few places available to send the most troubled of teens.

Many of its former residents would go on to become some of New Zealand's most notorious hardened criminals, including RSA triple killer William Bell.

Former resident Andrew (whose real name is also suppressed by the court) settled his claim with CYF earlier this year. He is blunt when describing Whakapakari as the worst of many state facilities he spent time in during his youth. "It was a f***ing hellhole," he says.

Two years after the last boy had been evacuated, CYF undertook a formal study of how effective the facility had been at reducing reoffending. Of the 69 boys who attended the camp in 2004, only one in five had not offended, and 61 per cent had racked up multiple convictions.

Simon, considered a nuisance and the instigator of the 1998 escape attempt, got his wish and was soon sent home to Dunedin. He says he's never talked with anyone from Whakapakari since, but can recall his last conversation with the three other failed escapees.

"As I left they told me 'Get us some help'. I did the best I could - I told mum, told the courts - but it got swept under the carpet and covered up."

It wasn't just Simon who tried raising the alarm. The quartet had shared their tale with the Whakapakari supervisor tasked with picking them up after the incident, who was concerned enough to blow the whistle. The supervisor's complaint included the observation that two of the four boys had, literally, pissed themselves.

Documents obtained under the Official Information Act as part of a wide-ranging civil suit against the Ministry of Social Development by Wellington law firm Cooper Legal on behalf of former Whakapakari residents, appears to show CYF's investigation into this incident was botched and the opportunity for justice - given the statute of limitations - has been lost.

The investigation report, dated September 7, 1998 shows the investigator didn't interview any of the boys, or the whistleblowing staff member, or the police, and instead preferred the explanation provided by Whakapakari director John da Silva.

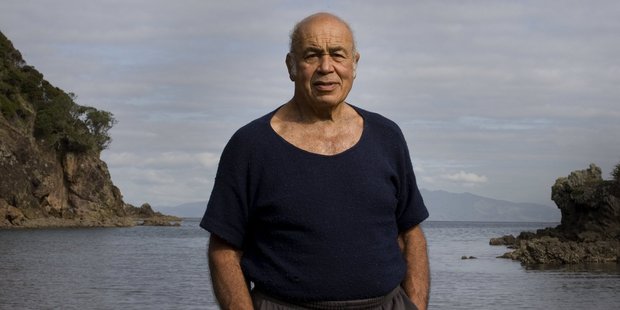

A former professional wrestler and star of 70s television staple On the Mat, da Silva had run Whakapakari on his family's land since the early 1980s. He claimed:

• Gunshots would have been audible to locals but weren't heard;

• The mock executions never happened;

• The gang member was actually just a "heavily tattooed local fisherman," and;

• The youths' work detail had been arranged by local police.

The investigator concluded that the complaints "need to be viewed in the context of police involvement of arranging the work with the aggrieved neighbour" and that the camp director was well-intentioned.

"At worst on Mr da Silva's part there was a concern to right the wrongs in order that the programme's credibility on the island could be maintained and the victim's loss [be in] some way atoned," the report said.

But the whistleblower was not satisfied and made another complaint, this time to the Commissioner for Children. Another investigation was opened in 1999, but despite finding serious problems with da Silva's version of events, the Commissioner was unable to reach a finding of facts as he too was unable to locate and interview the boys involved.

Crucially, the Commissioner's report shows that police formally denied any involvement in arranging the claimed work detail with the neighbour - a key plank of da Silva's version of events. The report also shows the final decision by police not to prosecute - delayed until July 2000 by the demands of an unrelated homicide investigation - was an almost shrugging of institutional shoulders.

The allegations "may well have some truth to them", the investigating officer told the Commissioner. "Nevertheless I would not be prepared to pursue a prosecution with evidence of this standard - specifically the unco-operative and unreliable nature of the complainants."

A review of the complaint files by the Weekend Herald shows Simon's version of events, unheard by police or CYF officials, broadly corroborates an evidential interview given by one of the boys and the initial complaint by the supervisor made in 1998.

Garth Young, chief analyst for historic claims at the Ministry of Social Development said he was unable to comment on what happened at Whakapakari - or the handling of the alleged mock executions - as the matter was before the courts.

He said the claims were being defended, but declined to elaborate on how CYF defended its conduct.

Putting aside questions of fact and liability, Young agreed that Simon's description of children digging graves and being menaced by dogs sounded horrifying. "I don't think any reasonable person would have any other reaction to something like that. Absolutely I wouldn't for a minute want you to get the impression that I or anyone would be defending that."

THE CAMP'S director, da Silva, now 81, still lives on Great Barrier Island and his Whakapakari camp has long been swallowed by the bush. He told the Weekend Herald that the neighbour at the centre of Simon's complaint was now deceased, and was simply a local fisherman.

"There seems to be a lot of accusations about ill-treatment floated around, and it's very difficult now - it's so many years ago - to find the people involved," he said.

He said his recollection was that the four boys involved seemed unharmed, despite the allegations of mistreatment.

"They all came back in one piece, there didn't seem to be anything wrong with them."

The former wrestler, who competed at the Olympics and in town halls up and down the country during a curious period in New Zealand history where professional wrestling was a legitimate local industry, defended Whakapakari by noting that no one had died.

"We certainly never lost a life, but we did have some pretty harrowing moments," he said.

His clients were the most difficult young people in the country, Da Silva noted. "Nobody has ever come up with a final solution to that kind of upbringing to magically make them good again."

Simon has a good word for the man who ran the controversial camp. "John Da Silva never condoned violence. I don't blame him for any of this " but he could have done with a second opinion."

According to internal CYF documents, for two years following Whakapakari's closure debate raged over whether the camp should reopen. In 2004 Jessie Henderson, head of the Grey Lynn CYF office was unusually frank in voicing vehement opposition. She said Whakapakari had relied on the charismatic leadership of Da Silva, but as he aged and suffered health problems he moved away from living on-site and his influence waned.

Something about the place seemed septic, Henderson said, noting that a highly-regarded and qualified former CYF social worker with an unblemished record also been accused of assaulting children after starting work on the island.

"The very nature of the programme - the remoteness, the primitive living conditions, the lack of managerial oversight and accountability creates an environment where otherwise sane people start behaving in an inappropriate manner."

Simon says he knows what the senior social worker means about the strange madness that occurred off the mainland. "The law on Great Barrier Island is a lot different from the mainland."

Nearly 20 years on, he says the memory of that day with the spade, thinking his body would fall into the hole he had dug, has never left him.

"Did it last two hours, did it last four hours? However many hours it was life-changing. It changed me."

He says he came from a violent home and had been accustomed to a certain amount of background violence, but this episode escalated matters.

"I have witnessed a lot of violent assaults, but not before this. It was all after this. After Great Barrier and Whakapakari I rebelled against the justice system and spend around 10 years in prison as a result," he says.

"A young man's life can be complicated, no doubt, but I found myself in more trouble than not after that."

He says after his initial complaint didn't appear to have been followed up, he thought no one would believe him and he still had flashbacks of the man with the shotgun who had made a point of writing down the four boys' names in a book before starting his interrogation. "I kind of think no one cared: People thought we were trouble. No one ever followed anything up. It was only a whole year later the police knocked on the door asking questions," he says. "At the time I was very fearful about what had happened. But I'm not afraid to talk about it now.

"At the end of the day I'm now grown up, with kids of my own - and you just can't do that to children."

Some former residents talk of Whakapakari helping to turn their lives around, but the recollections often come with hints of the problems that would later consign the facility to the dustbin of history.

Former resident Zascha Paraku recounted on Oldfriends his 1989 placement, saying though some might call the camp a "doomed place", he had a different experience. "For me I thoroughly enjoyed every minute I spent here," Paraku said.

The recollection ends with a shout-out to friends met at Whakapakari, including Calvin who, "got the meanest hiding and was shipped to hospital".

THE SIGNS were even broadcast to the rest of the country in 1992, during an hour-long documentary on TV One. Half-way through Breaking the Barrier - a broadly positive take on Whakapakari, emphasising the facility as a last chance saloon before troubled youth entered the justice system - the programme's narrator takes a short but extremely dark detour.

"The camp has woken up to the shocking news that one of the boys, desperate to get sent back to the city, has mutilated himself with a butcher's knife. 'Rat' has taken the extraordinary step of circumcising himself."

"Rat", no older than 15, with his face blurred out and a bloodied towel around his waist says "this place is a shithole, man".

Da Silva is observed fingering the instrument of mutilation, saying "the knife is not very sharp".

He and other camp supervisors appear to have no idea what triggered such an extreme reaction.

Aboard the rowing boat taking the teen to whatever he calls home, the boy who crudely circumcised himself raises his arms in triumph.

"See you in Auckland!" he shouts.

My son was sent there and after reading this write up I will be asking for a full report

ReplyDelete